RESEARCH

Developing sweet chestnut value chain in The Netherlands

by APCM students 2021-2022, Marco Verschuur & Euridíce Leyequíen Abarca (eds)

This research paper is the result of an assignment for students of the Master Agricultural Production Chain Management (APCM), commissioned by the EU-Farm Life Project and Göran Christiansson (Kwekerij Culinair) in collaboration with the Van Hall Larenstein University of Applied Science to conduct a rapid chain appraisal on the potential of the sweet chestnut value chain in the Netherlands.

Sweet chestnut

The sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill) with an elongated, elliptical form with brown colour and an intense flavour is the only edible native genus in Europe and its cultivation has existed for the past 400 years. Sweet chestnuts are mainly grown in the loamy and sandy soil in the Netherlands with medium or high fertility. The old chestnut trees are existing in public areas, such as Waterberg national forest in Arnhem, purposely to be consumed by the neighbouring inhabitants. Sweet chestnuts can be used as edible fruits for human consumption and as a source of timber. Worldwide, sweet chestnut is produced in Asia (China and South Korea), North America, and in Europe mainly in France, Italy, Spain and Portugal accounting for 10% of the fruit production globally. Sweet chestnut fruit is highly valued and widely consumed in America, Asia and Europe. The production of sweet chestnuts has decreased since 1960 due to the decline in consumer value. However, recent studies show that there is a revival of sweet chestnut production in Europe due to its new market potential and contribution to agroforestry systems. The sweet chestnut production chain is in an infancy stage in the Netherlands with little stakeholders’ awareness (producers and consumers) of its potential. There are a few seedling producers who supply to a few chestnut growers.

Currently, sweet chestnut as a high shade-tolerant tree is grown all over the Netherlands in forested areas and agroforestry systems. The forested areas allow the natural, highly diversified ‘polyculture’ environment to mimic the ecosystem. The types of agroforestry are divided into food forests, silvo-pastoral and silvo-arable systems, where silvo-pastoral combines animal production and perennial crops (i.e., trees and shrubs), whereas silvo-arable integrates annual crops and perennial crops. Nature-inclusive farming systems can be silvo-pastoral or silvo-arable.

In the value chain structure of the sweet chestnut sector, the primary activities consisted of seedling production, followed by cultivation, storing, sorting, packaging, transportation, and marketing. The barriers to success in the sweet chestnut business include insufficient information for producers, retailers and consumers. In the Netherlands, there is insufficient information about the chestnuts, stakeholders, and information flow in the sweet chestnut value chain.

Research approach

The objective of this research paper was to advise stakeholders about the potential of edible chestnuts and related products and services in the Dutch Market along the value chain e.g., product, production, processing, distribution, and substitutions. This was achieved through conducting Rapid Chain Appraisal to identify the potential of sweet chestnuts and related products and services in the Dutch market along the value chain. A Rapid Appraisal is a participatory approach used by governmental and non-government organizations to gather information within a limited time. This approach was used, because the mini research was to be conducted within 3 weeks by an interdisciplinary team. During the study aspects such as the roles of various chestnut stakeholders, the current chestnut governance structure in the value chain, product and services, current production system, substitute products, and the extent of consumer awareness of sweet chestnut products were studied. The study was carried out in the provinces of Gelderland, Noord-Brabant and Utrecht in the Netherlands. The three provinces were selected, because they consist of large, forested areas and this could be used as an example to the rest of the country. Planning and preparation were done in the first week, followed by data collection and processing in the second week and the third week was for data analysis and presentation of results.

Purposive and snowball methods were used to identify and select thirteen (13) stakeholders in and around the chestnut or comparable value chains to be interviewed during the study. These interviewees comprised seedling producers, chestnut producers, processors, distributors and supporters such as government officials, nut association, farmers’ union and researchers. Secondary and primary data were collected. The secondary data was collected by reviewing existing literature on chestnut value chains through desk studies using search engines such as GreenI, Google Scholar, ResearchGate, and CABI. Journals, books, and articles related to the topic were reviewed. Primary data was collected from selected participants through rapid appraisal (RA) tools such as interviews and observations. The obtained data was qualitative and processed to allow transcribing and coding into developed themes.

Sweet chestnut chain

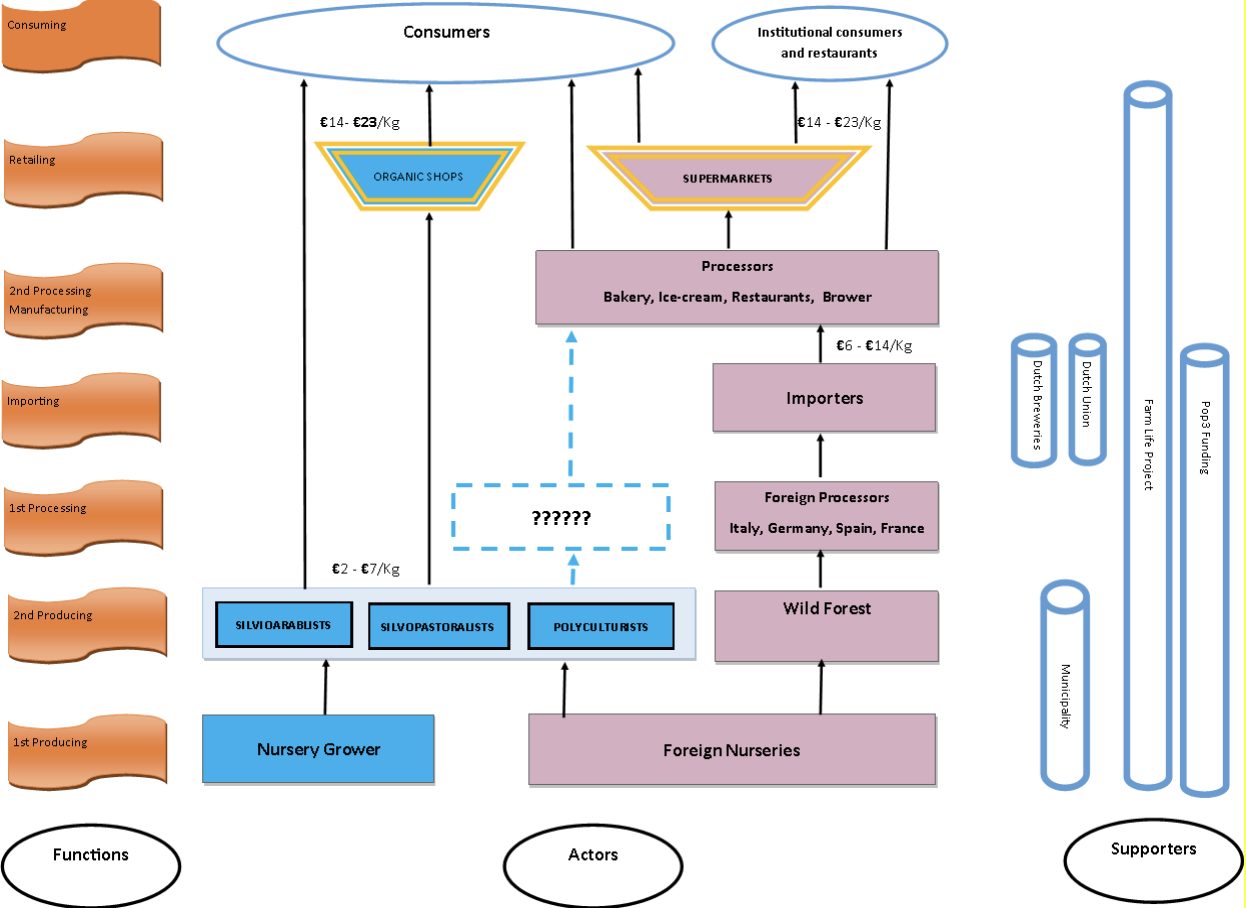

From the value chain analysis of the potential chestnut value chain in the Netherlands revealed a value chain map of various actors, supporters and influencers (Figure 1). Four distinct chains were identified within the sweet chestnut products flow. Sweet chestnut value chain actors include nursery growers, chestnut growers, processors (product manufacturers, such bakeries, breweries, snack and icemakers), importers, retailers (organic shops and supermarkets), and consumers, including institutional consumers and restaurants. The identified supporters and influencers include Dutch Farmers’ Union (LTO-Noord), Municipalities, Farm-Life project and POP3-funding.

Additionally, from the value chain analysis, it was found that the chestnut value chain in the Netherlands is highly influenced by an import flow of whole chestnuts and flour, especially from France. Domestic products flow through niche market channels. There is presently no first-level processing (drying, milling) of chestnuts in the Netherlands. The study also showed that a well-structured network and coordination between the stakeholders in the sweet chestnut value chain in the Netherlands does not exist.

Also, the study found that there is a strong relationship (informal) between nursery growers and input suppliers as well as with nursery growers and chestnut growers. There are no clear and distinct relationships between chestnuts retailers and consumers. Organic shops stock also other products, so the relationship with consumers is not directly linked to sweet chestnut purchases. The relationships within the sweet chestnut value chain are in infancy but growing as more farmers incorporate sweet chestnut growing into their farms. The flow of information among the sweet chestnut value chain players is strong due to the presence of a few players although it is still at an informal level.

Figure 1: The current sweet chestnut value chain in the Netherlands.

The propagation methods, observed during the farm visits and transect walks, are directly by seed or vegetatively. There are three different methods: (a) in the nursery and in the open environment as self-propagation in nature, (b) direct planting from the seed, and (c) nursery seedling production.

The study revealed that sweet chestnut production in the Netherlands is still at its developing stage. These chestnuts are consumed raw or in a roasted form and some are processed into flour that can be used in making bread or used as ingredients in culinary arts. The services currently available for potential actors in the value chain are training, financing, and consultancy.

Since a sweet chestnut is gluten-free, it is used in making flour for baking, substituting partly wheat flour. Just as buckwheat, oats, spelt, corn and teff are also used for gluten-free flour. Interviews with bakeries and restaurant owners revealed that chestnut flour has a dry texture and distinct taste that must be improved on before being used for baking. This can be done by blending chestnut with other products such as flax seeds or eggs and goji berries respectively. The chestnut chain development can learn from the developments made in the introduction of the walnut and hazelnut chains in the Netherlands.

The findings showed that the level of awareness among the consumers is very low due to the knowledge gap on its preparation and usage. The majority of the chestnut consumers in the Netherlands are mainly elderly citizens the ones more aware of the chestnuts. Interestingly, one of the key informants stated that Dutch people consume what they know (what we don’t know, we do not eat). It was also found that sweet chestnuts are a niche product found in specialized shops such as bakeries, organic shops, and direct sales in pre-established connections between producers and consumers of the sweet chestnuts.

From the survey, the sweet chestnut-based products in the Netherlands are chestnut ice cream, cookies, chestnut beer, chestnut shower gel, burgers, vegan crockets, “bitterballen”, chestnuts paste, fermented Goji berries, chestnuts cider, chestnuts souffle, chestnut fudge, and tempeh. There are also chestnut flavouring products such as sweet chestnut honey, chestnut crockets, and chestnut milk.

The survey identified gaps within the sweet chestnut value chain, these include the first and second levels of production. There is only one specialised nursery grower and there is no specific chestnut cultivar favourable in the Netherlands, the grower produces seedlings from different varieties sourced from Turkey, Japan, France and Italy. The sweet chestnut production volume is still low, because of few farmers who have young trees, and the existing production is mostly picked from the nature-inclusive forest.

The second gap that needs to be addressed is the first processing industry (drying, milling), because the current production is locally processed. Furthermore, raw chestnut production has only three months of shelf life, therefore, this needs to be improved with proper storage. Existing rules and regulations hamper the implementation of agroforestry in certain provinces and municipalities, and the latter has been experienced by some of the interviewees that were not allowed to plant trees in open landscapes. Also, another bottleneck is the initial investment and the first years of the implementation of agroforestry, in this case with sweet chestnut trees since a chestnut tree takes almost three to five years to give the first harvest.

Future developments

For a steady growth of the chestnut value chain in the Netherlands, production of chestnuts must increase substantially in the coming years as the demand for chestnut products increases. To accelerate the adoption of chestnuts into the current Dutch farming systems of crop and livestock production the adoption of agroforestry systems is recommended. By increasing the supply of chestnuts, the diversification of chestnut products such as chestnut burgers and chocolates (fudge) is important in order to attract more consumers and hence increase the demand. This can be achieved by increasing processing where private processors can fill the gap, as well as other actors that can be motivated to take up the processing role in the chain.

For the chestnut value chain to be sustainable, an integrated chain approach is required. This involves the collaboration of stakeholders to jointly provide a conducive environment for investments along the entire value chain. These initiatives include improvement from all input suppliers to consumers, producer associations, production and quality of chestnuts, trading sector, and market information system. A robust chain coordination initiative is strongly recommended to coordinate actor relations in the value chain which is currently fragmented.

The Farm Life project is addressing the challenges in the sweet chestnut production through the adoption of agroforestry systems (and food forests). Building strong chestnut partnerships among supporters (Farm Life project, government, research institutions, financial institutions) and potential actors (nursery, chestnut producers, processors, manufacturers, wholesalers and retailers) is strongly recommended. This partnership is recommended to involve a public-private partnership (PPP) through a multistakeholder platform to strengthen the sustainability of the sweet chestnut value chain in the Netherlands. The producers are more likely to benefit from this partnership through gaining production and food processing knowledge, financial support and market access.

Harmonization of policies by the government from the national level to the municipality would provide equal opportunities for farmers to access available resources. Also, increasing public awareness will increase the consumption of sweet chestnuts and sweet chestnut-based products in the Netherlands. Public awareness can be created through the use of social media, provision of opportunity to taste sweet chestnut products in festivals, advertising, re-branding chestnuts products, and incorporation of chestnuts with other products will attract more consumers. Moreover, open-air markets in the city centres and along the streets will attract consumers who like to try out fresh or roasted chestnuts.

To stimulate the development of the sweet chestnut value chain from both the supply and demand side, disseminating of information about the sweet chestnut value chain, using various means, and including different stakeholders in the value chain are the proposed interventions.